"It seems impossible to avoid the impression, when observing the current state of the digital game industry, that gaming and reading are not that far apart. Works that combine games and literature may be difficult to define, but this difficulty is also an inspiration; a sign that we are looking at a new form of expression." Nokturno's guest curator 2020 game journalist Aleksandr Manzos presents a selection of works combining game art with literary elements.

The word “game” (which will be used throughout to denote digital games) often conjures images of playful interactive franchises such as Fortnite and Minecraft, created to simulate competition, conflict, or construction. In the end though, digital games — as opposed to board games or role-playing games, for instance — are simply experiences made possible by a computer or similar device. Nothing in the form of a digital game defines its content. The definitions exist in the imaginations of the creators and players.

Our imaginations are shaped by the culture we live in. In Japan, anime and manga traditions strongly influenced the development of distinct characters in Pac-Man-era coin-operated arcade games (c. 1980). At the same time, the iconic tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons swept the Western world, leading to PC games such as Wizardry (1981) incorporating features such as complex simulated fighting systems. Both of these historical ancestries are still visible in modern games.

Literature and its ways of narration and communicating ideas were also a key source for some early games. The text-based adventures of the 1970s and 80s offered experiences that differed from other games of the era. The game A Mind Forever Voyaging (1985) by Infocom commented on the Reagan administration’s politics by imagining their long-term impacts.

Pioneering works such as this used language to describe things that the technology of the time could not visualize. Text adventures were also called interactive fiction for this reason. They remind us that digital games have always possessed literary roots, which lay dormant for many years with the advent of tech-driven, ambitious, and increasingly cinematic games.

“Games and literature can glean a great deal from one another.”

The game industry still relies heavily on spectacle and hype. In the 2010s, an alternative thankfully emerged: independently published (indie) games. The Internet offers channels for free publication as well as reaching groups of people with an interest in different forms of expression. This has also lead to a resurgence of literary games, and the expansion of the very definition of a digital game. Anyone can do anything for anyone. Where old-school textual adventures limited themselves mostly to the realm of speculative fiction and included difficult problem-solving, a modern text-based game can take a vast array of forms.

I will introduce six literary games below with an emphasis on their form. It is not the only way to approach the intersections between games and literature, but form or preconceptions of it may prove a stumbling block when getting acquainted with the subject. Games and literature can glean a great deal from one another, but the transition from the former to the latter may seem difficult, especially for people to whom the methodology of digital games is unfamiliar.

Hyperlinked Text: howling dogs (Porpentine 2012)

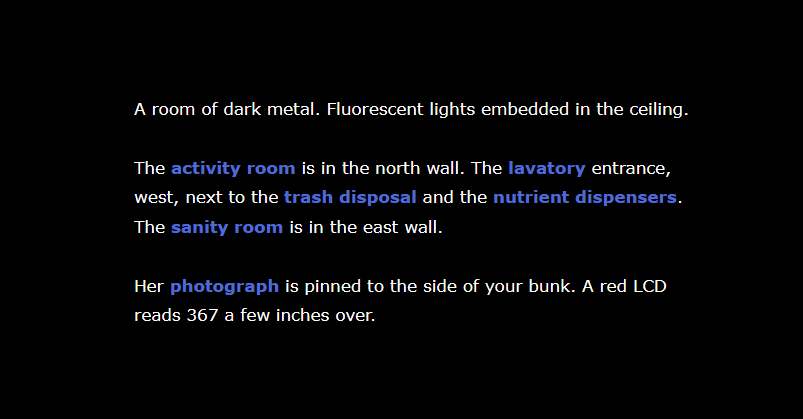

Early interactive fiction was born in a time when computers were operated by inserting cryptic commands into a blank prompt. Playing these games these days is just like returning to the old DOS world: if you don’t know the logic of the commands, the system is impossible to use. It is fitting that the current age of hyperlinks has produced its own forms of text-based games. Games created with a development tool called Twine are essentially html pages, usually playable directly in-browser.

Porpentine’s howling dogs is a prime example of a Twine game: a short narrative that expands one text fragment at a time, according to which hyperlinked word or sentence the player chooses. The unknown protagonist connects themselves into some kind of virtual reality, day after day. Every time the machine transports the player into the experiences of another person’s life — usually in some extremely remote place and time. The amount of choices in howling dogs encourages the player to complete it more than once, to approach it from different perspectives (Retry, in DOS terms).

“The game shows abstract pixel art at the beginning of each chapter, but the actual events of the game are presented solely in textual form.”

The absence of choices can also be part of the narrative dynamic. At the start of each day, the protagonist can do things such as wash themselves or look at a photograph before plugging into the machine. It is, however, impossible to even attempt to exit the space. Does the game take place in some sort of prison cell, or does the protagonist have such psychological difficulty with leaving their house that it doesn’t even occur to them? Denying choice guides interpretation just as choices themselves do.

A Twine game may include some visuals, but they tend to play a very small role. This is also the case with howling dogs. The game shows abstract pixel art at the beginning of each chapter, but the actual events of the game are presented solely in textual form. This sets it apart from another type of game, known as a visual novel.

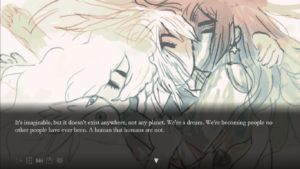

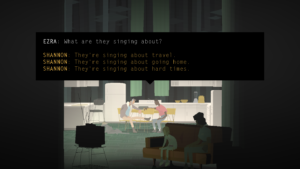

Visual Novel: We Know the Devil (Worst Girls Games 2015)

The term “visual novel” is a little misleading. It describes a distinctive text type that resembles a sort of illustrated play script as much as it does a traditional novel. The visuals are static: the backgrounds depicting the locations and the expressions and positions of the characters only rarely change. The text, in dialogue forms, takes up most of the player’s attention.

The unusual form comes from old Japanese dating games, where the player could choose between various partners. The interchangeable backgrounds and characters were an easy way to create story paths without every variation having to be illustrated from scratch. No wonder that small-budget indie developers have made the form their own, just exchanging dating fantasies with more diverse approaches to gender and sexuality. Visual novels are in fact quite popular in the LGBTQ developer community.

“Replayability, a key characteristic of games, is present in a work that is a sort of novel, at least in name.”

We Know the Devil by Worst Girl Games follows the story of three teens at a summer camp. The trio feels excluded from the others and ends up spending the night in a remote cabin. The opening is a horror story trope, but We Know the Devil takes it in surprising directions. Outer and inner events become entangled, and the characters’ search for their identities is likened to an occult ritual. The poetic script also helps to blur the differences between the supernatural and the personal.

Typically for visual novels, We Know the Devil focuses on the interpersonal interaction between the characters. Addressing the arising events and thoughts is at least as important as direct action. Also typical is the fact that the occasional choices posed by the game lock in the story’s progression, namely which character’s arc is to be followed. We Know the Devil is designed to be playable in three distinct ways. Replayability, a key characteristic of games, is present in a work that is a sort of novel, at least in name.

Adaptation and Multiple Choice: 80 Days (inkle 2014)

Howling dogs and We Know the Devil are both closer to literature than games in that every player goes through roughly the same stories while playing through them, even if the details change according to each individual choice. A literary game can still be truly free-from, as in the case of 80 Days by inkle.

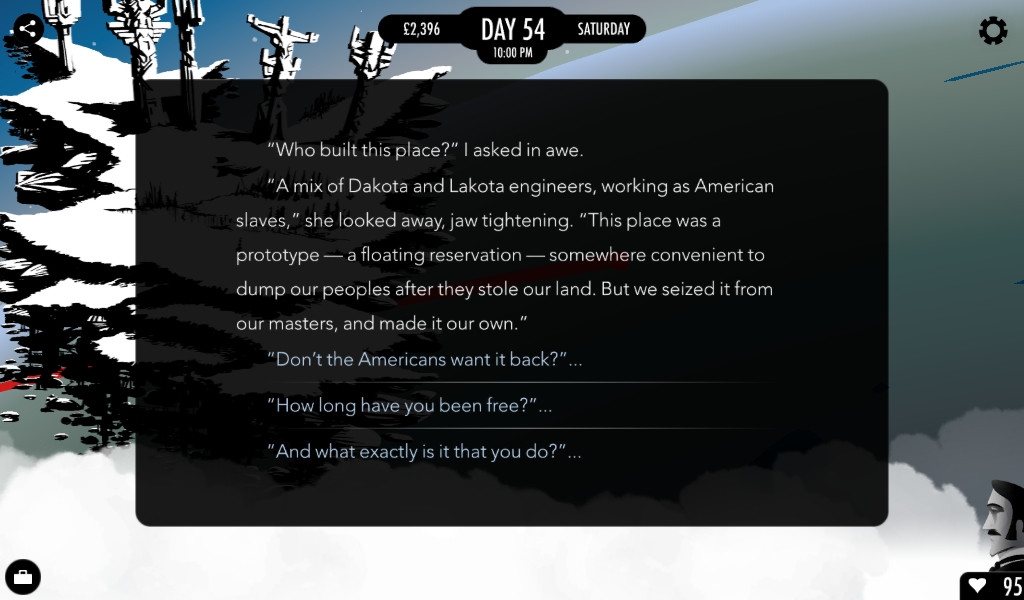

80 Days is an adaptation of Jules Verne’s 1873 novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, where a gentleman named Phileas Fogg and his servant Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate the globe within said deadline. Instead of there being only one route to take, the game allows the player to visit dozens of locations, from Ulundi to Yokohama and from Helsinki to Tehran. Each destination involves its own twists and turns, the outcomes of which are determined by the player’s choices. 80 Days is like a collection of hundreds of miniature short stories whose scope cannot be exhausted by one or even several playthroughs.

Verne’s original tale of imperialist colonialism has not stood up to critical examination for decades. What makes 80 Days an interesting adaptation is its rewriting of everything except the premise. The inhabitants of the various locations around the world describe themselves in their own words. Fogg’s cultural stiffness is shown in a ridiculous light. The player, as the loyal Passepartout, is given many opportunities to learn from the people they encounter.

The open form of 80 Days relieves some of the weight of the original setup of a race (pun intended). Flying around the planet in eighty days is a fun game challenge as far as it goes, but the journey may be at its most enjoyable when the player focuses on what is most important in travelling: expanding one’s worldview as the world is revealed. The interactive format of 80 Days is not only a fun way to “game-ify” a historical novel, but also a way to change our experience of the undercurrents of the original book.

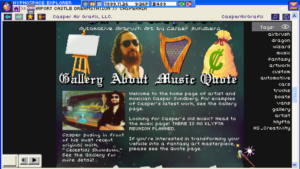

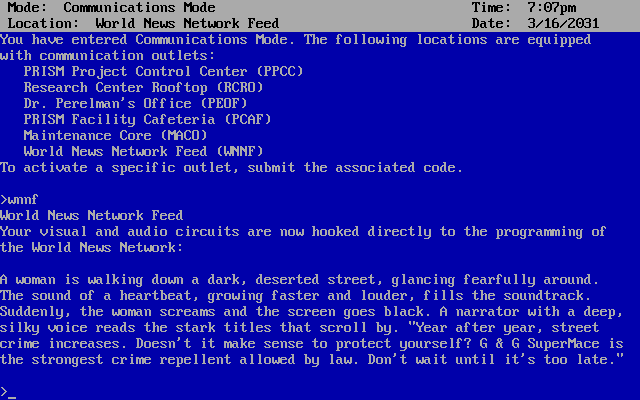

Archive Mystery: Hypnospace Outlaw (Tendershoot 2019)

Literature that is composed of numerous parts or sections is often labeled difficult or at least experimental. The common belief concerning novels, for instance, is that they are clear-cut stories that run from beginning to end, not a mystery that needs to be solved based on fragments and clues. And yet the challenge itself may motivation to engage with the text. This is true for Tendershoot’s Hypnospace Outlaw.

“The world of Hypnospace Outlaw is simultaneously recognizable and yet unfamiliar.”

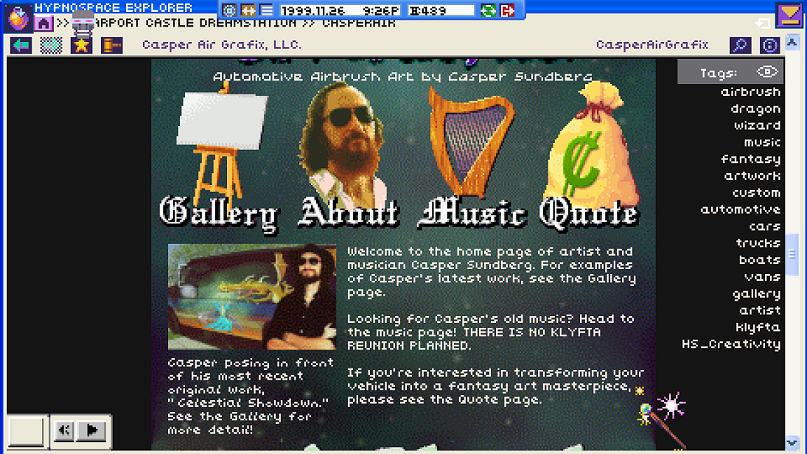

The game is like an internet archive from a fictional version of the 1990s. The player acts as a moderator whose job it is to seek out offences such as piracy and harassment, on dozens and dozens of websites. It gradually becomes apparent that the deeper problems may lie rather in the web designers rather than the users. The moderator soon becomes a detective.

The world of Hypnospace Outlaw is simultaneously recognizable and yet unfamiliar. Fan sites for awful bands, homepages showcasing people’s hobbies, and other remnants of the 90s will make many players laugh, because they feel real. Just as on the early internet, all the images are painfully pixelated and various visual forms are combined fearlessly.

Playing Hypnospace Outlaw may feel like a nostalgic reboot, but ends up revealing the constancy of human nature. Clunky amateur web pages created with services such as Geocities or Angelfire have made way for meticulously curated social media accounts, but the desire to speak about ourselves in impressive ways hasn’t gone anywhere.

Hypnospace Outlaw proceeds along quite freely. The archive can be approached from many directions, and many pages will certainly remain hidden. It is the abundance of content that makes the experience so appealing. The player surfs the pseudo-web guided by the moderator tasks, but each page the player reads affects the picture they paint of the in-game world in their head. Hypnospace Outlaw is like a stack of puzzles strewn across the floor. From these scattered pieces, each player composes a complete picture that is slightly, and perfectly, disjointed.

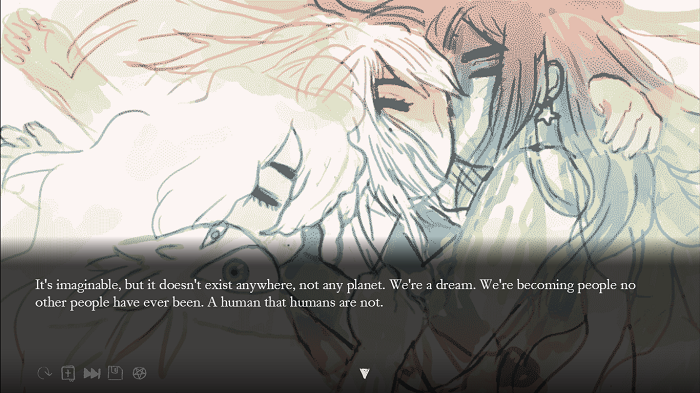

The Great American Game: Kentucky Route Zero (Cardboard Computer 2013–2020)

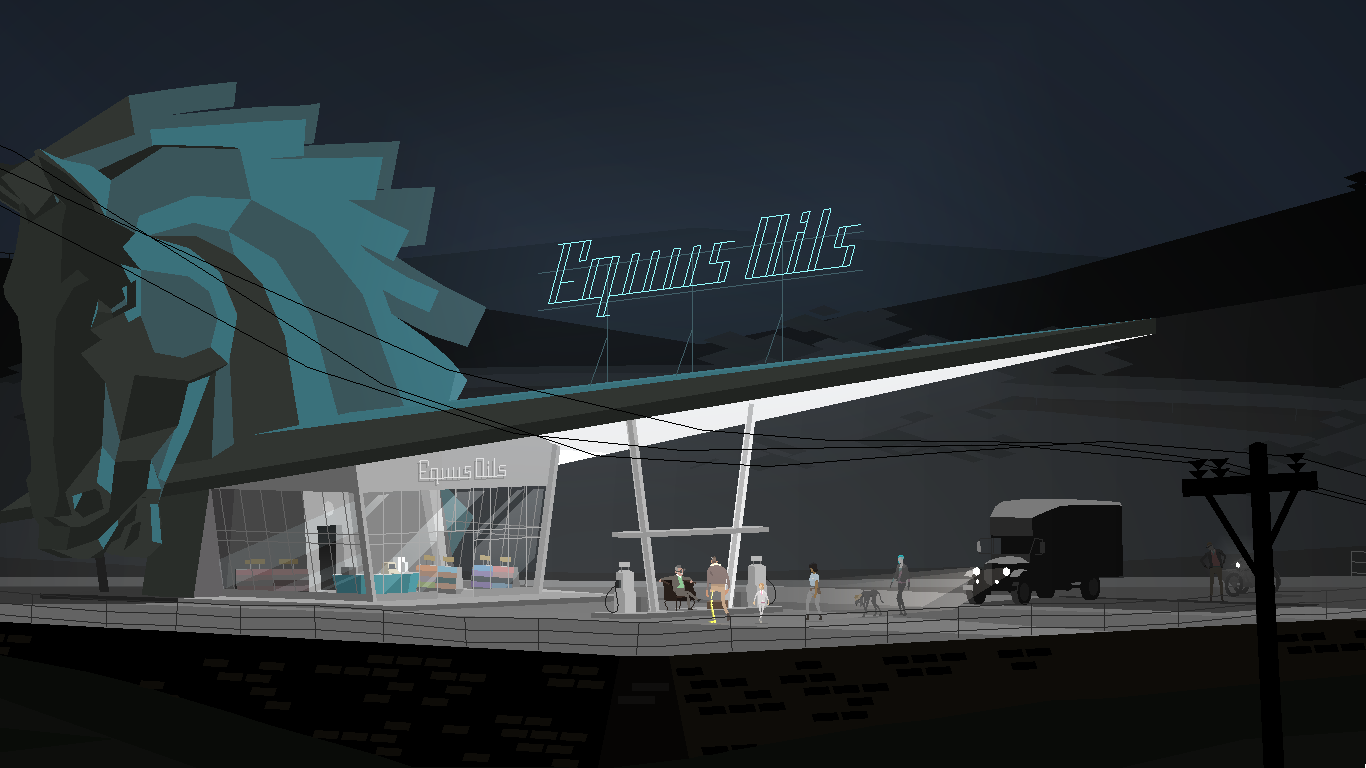

The concept of the “Great American Novel” presents a two-edged issue. One might, for instance, focus on the difficulty of its definition and the problematic nature of any over-generalizing national canon. On the other hand the term can be used to immediately conjure an impression of the themes and aspirations of a given work. With this mode in mind, it is not excessive to claim that Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero is the closest game equivalent to the great American novel.

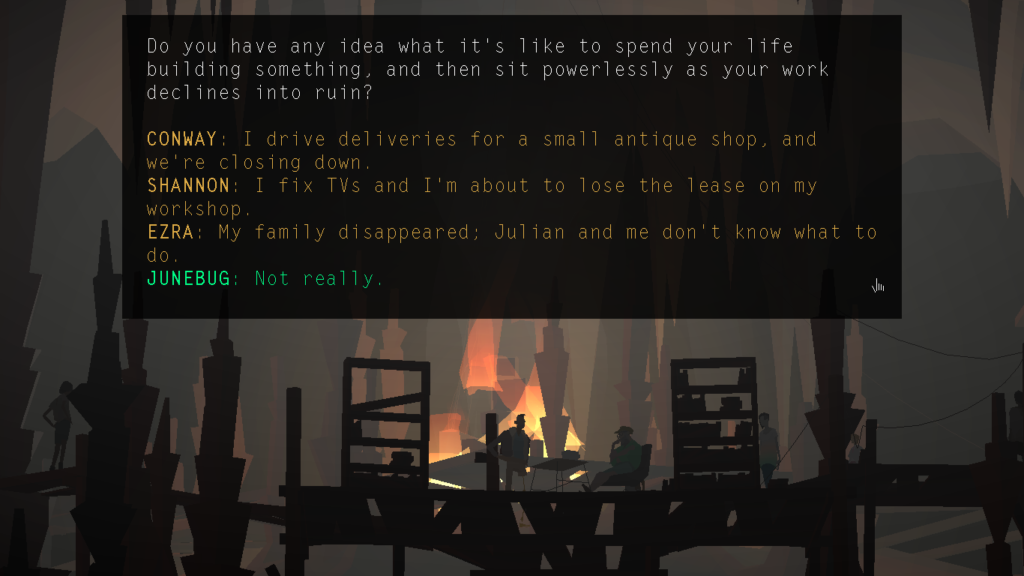

Kentucky Route Zero is framed by a narrative of an aging courier called Conway, on his final delivery run. Much like in 80 Days, different interactions on the road form the backbone of the experience, not reaching the destination. The game’s backdrop is based on Southern Gothic and magical realist traditions: a group of travelers who have fallen outside of society are wandering in the aftermath of a financial downturn; it is hard to discern what events in the game should be taken literally and which ones as visions or abstractions.

“This solution underlines the game’s picture of the world and the many phases of human existence as mysteries that we may never be able to solve, merely illuminate from different angles.”

The game’s fluid sense of reality was highlighted by the fact that it was published in several instalments over seven years. The mysteries raised by a single scene went unanswered for long stretches of time, or remained unsolved entirely. Tying together destinies that appear separate and showing their similarities in wide panorama is what is most important.

The segmentation of Kentucky Route Zero into acts and scenes is borrowed from the world of theater and drama writing. Each locale is like a carefully considered set, where every detail serves the scene. The lines are not predetermined; it is up to the player to choose them. The broad strokes of the main plot are set in place, but within that framework there are hundreds of routes up the dialogue trees, which alter how certain characters and situations turn out.

This solution underlines the game’s picture of the world and the many phases of human existence as mysteries that we may never be able to solve, merely illuminate from different angles. Perhaps that is the most truthful description of a certain place and time of which we are capable.

Challenging Narration: Pathologic 2 (Ice-Pick Lodge 2019)

Of the games presented above, only Hypnospace Outlaw sets conditions for how to proceed. In all the others, the focus is on the narrative, not the challenge. But a literary game can swing over to the opposite end of the spectrum, as Pathologic 2 by Ice-Pick Lodge demonstrates.

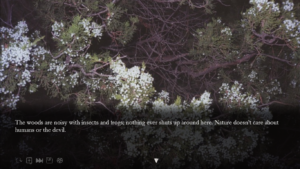

Pathologic 2 is a retelling of its namesake predecessor, from 2005. Both games tell the same story: a plague breaks out in a small village somewhere on the remote steppes of Russia.

The epidemic acts as a catalyst for the player to interact with the various characters in the town. These are often written to reflect certain opposing ideas and values: nature vs. science, the individual vs. the community, tradition vs. progress. All these are expressed as a rich, philosophical multiple choice dialogue which on its own is enough to make Pathologic noteworthy.

“While Pathologic 2 offers many volumes’ worth of deep-delving text, it makes survival so hard that accessing it all becomes impossible.”

But the plague is more than just a cerebral challenge. The character has to eat, rest, and stay healthy as a deadly disease decimates the city. The game’s difficulty is set to make you feel on the brink of failure constantly, on purpose. There is never enough food, the clock tick down without mercy, and important contacts get sick if you don’t take care of them.

While Pathologic 2 offers many volumes’ worth of deep-delving text, it makes survival so hard that accessing it all becomes impossible. The player must leave central characters to die when resources fall too low to help everyone. Interactions whizz by, as half the day is spent hustling for a single chunk of bread.

The challenge in Pathologic 2 is not meant to be a nuisance, it is a method of committing the player to the narrative. Weighty ethical and societal questions are not left vague or vapid, as the player has to stand behind every choice they make with concrete actions. A game designed in this way demands a great deal of its experiencers, but it also shows the potential of intersections between digital games and literature.

2020 – the Decade of New Literacies?

These games and others like them have broadened our shared imagination concerning what literary games can be. There is no dearth of models for creating such works in non-mainstream game culture. The central question is now: will they remain in the underground?

A literary game is a hybrid that seems to repel many readers with its game-ness and many gamers with its literary-ness. Strictly categorizing interactive and non-interactive works feels honestly artificial, in a time when our lives are much intertwined with information technology, the internet, and social platforms. Interactive reading is already a part of our everyday lives.

In an article from 2010, literary theorist N. Katherine Hayles approached the role of careful close reading in an increasingly hectic digital age: “Reading has always been constituted through complex and diverse practices. Now it is time to rethink what reading is and how it works in the rich mixtures of words and images, sounds and animations, graphics and letters that constitute the environments of twenty-first-century literacies.” Hayles is not speaking of digital games here, but the description suits them rather perfectly — not least because they require a certain competence in order to be fully experienced.

As literature and digital games intermix, we need to develop our comprehension of both worlds — and build bridges between them.

Aleksandr Manzos is a journalist focused on digital games. He has written for Pelit game magazine for over a decade and is the author of three books on digital games in Finnish. His homepage can be found at amanzos.com