The first issue of Nokturno in 2022 explores place attachment and draws on various historical traditions of expression. The new editor-in-chief takes charge.

When the commemorative event of the 700th anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s (1265–1321) passing took place last autumn at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University, there was (at least) one android among the guests. Ai-Da, “the world’s first ultra-realistic robot artist”, had generated for the event a selection of poems inspired by the textual mass of The Divine Comedy. The robot also recited its own poems at the event.

The framing and coverage of the exhibition was somewhat shamelessly anthropomorphic. The primary task of the poetic robot was conceived of to strengthen and prop up the boundaries of the human territory. According to Gervase Rosser, curator of the Dante exhibition, the purpose of the collision of artificial intelligence and the poetry of Dante was to challenge the viewer to consider, for example, the nature of creativity and the value of human relationships. For example, the visual artist Nico Kos, who wrote about the exhibition, perceived Ai-Da’s poetry as a “ghost echo” of Dante’s oeuvre rather than an artistically convincing, original poetic expression. Nevertheless, Aidan Meller, the developer of the Ai-Da robot, said in an interview with The Guardian that the pace of progress in artificial integelligence based language models is “deeply unsettling”. Meller hypothesized that distinguishing artificial intelligence based texts from human text may prove to be a virtually impossible task already in the near future.

The anthropomorphic framing seems to have taken the public attention from that which in the whole case is by far the most interesting dimension. The poems generated by Ai-Da, and especially the recorded utterances of the poems, are, to say the least, somewhat startling. In the non-mouth of the ultra-realistic non-human, the highest achievements of (human) literary endeavors take a form, or, rather, territorialise an area the stepping into which require some courage on the part of the human reader-listener. The ontological registers of human and non-human get all messed up. The literary history repeated by the algorithms of the robot artist opens the way for human-to-non-human collisions, crossings of boundaries from eye to “eye”.

In the works of the first issue of Nokturno in 2022, literary history and digital dimension form new, unprecedented connections with each other. Along with time and history, the question of place is also emphasized; the works of the issue are connected by questions of roots (or rootlessness) and also tradition(s) – times and places in history.

The issue begins with Terhi Marttila’s interactive digital work Transplanted, which utilizes web browser’s speech recognition technology. According to the author herself, the work maps the meanings of place attachment and moving. From a reader’s point of view, the key feature of the work is the question of communication: what kinds of forms of communication does the specific digital expression of the work enable and produce, and what effects does this have on the experiential dimension of the work? Having a conversation with the work – or, rather, trying to establish a communicative relationship with the work – creates the impression of simultaneous presence and distance. The communicative connection produces its own singular spatiotemporal reality.

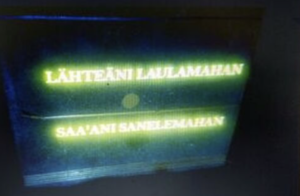

In Maija Saksman’s work R=U=N=O L=A=U=L=U K=I=E=L=I (P=O=E=M S=O=N=G L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E), the Carelian tradition of rune singing connects with, on one hand, the tradition of language-sensitive expression and, on the other, mundane digital phenomena of today. The seven-part ensemble, which leads deeper and deeper into the nooks and crannies of one’s browser, follows a three-pronged path of sung poetry. The participatory work, which encourages the reader-listener to sing along, aims, among other things, to transform the singer into “some kind of poetic song creature, a song tree”. Later, for example, the “language philosophy of flowers” is discussed in the form of a rune song. Within the work one can progress either via provided hyperlinks or along a path indicated by QR codes leading from one page to another.

Petri Keckman’s work Eino Leino, riimikeino (Eino Leino, a rhyme vehicle) asks what a digital artist can and should do with a canonized literary tradition. Drawing on Finnish national romanticist poet Eino Leino’s (1878–1926) vast verse material, Kekcman’s poem generator produces hilarious, rhymed nonsense. The verse robot is far from “ultra-realistic”, but there is still something extraordinarily appealing about the collision of the canonized expression and a generator that couldn’t care less about the values of canonizing.

By combining sound, image and text Lotta Nevanperä’s and Pelle Romantique’s work Par avion – sarja erootillisia postikortteja (Par avion – a series of erotical postcards) flirts with the phenomena and aesthetics of the turn of the 20th century. The multidisciplinary work creates a unique, even fantastic world, in which imaginative photomontages are combined with the mysterious arrangement of the accompanied poem reading. The work draws on the aesthetics of the authors’ poetry collection Konerunoja (Machine poems, Enostone, 2021). The music heard in the work is an excerpt from Pelle & Romantiks’ “literary record”, which will also be released this year, and which will also be titled Konerunoja (Helmi Levyt).

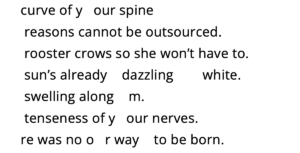

X-Ray By Two, an ensemble of two text-based poems by John Grey, an Australian poet, brings to life a slice of old countryside with its expression, but the means of imaging turn out to be anything but perfect. A linguistic “X-ray exposure” of poetic language strives to stop the movement of the world depicted into an image, but the end result is marked by textual gaps, indicative shapes, and the innate inaccuracy of the imaging apparatus – that is, language. The gaping rhythm of the texts produces hybrids gesturing in the direction of pictorial and/or pattern poetry and concrete expression. At the core of the poems lies the age-old, still relevant question concerning the multifaceted relationship between language and the world.

The issue ends with the gradually accelerating poem video Betty the Builder by Maailmanlopun Kahvila, a multidisciplinary poetry collective. In the gloomy texture of the work, the contemporary phenomena of anxiety symptoms and social pressures take a form of a performance that, in all its intensity, reaches out to the viewer’s bodily experience. Havalusa’s unassuming music carries eventually in to the smoky grimace that closes the work and, at the same time, this issue of Nokturno.

At the turn of the year, Virpi Vairinen, the previous editor-in-chief of Nokturno, handed the post over to yours truly – a humble thank you for the trust. Thanks also to Virpi and the entire Nokturno team for your first-class work over the preceding years. It is much easier to take on new things with all of you by my side.

Some things will most definitely stay the same: Nokturno will continue to be published four times a year, and anyone can still offer works anytime for publication at Nokturno. My professional background is in literary research and literary criticism. What may be expected to change on this basis is the perspective from which works offered on and published in Nokturno are viewed and framed. My aim is to emphasize the view of an active reader in the field of digital and experimental poetry. Wishing you a bright, warm and beautiful spring, dear active reader!

Miikka Laihinen

(Image from Lotta Nevanperä’s and Pelle Romantique’s work Par avion – sarja erootillisia postikortteja.)